March 1, 2024

KATHMANDU – Before the Covid pandemic, the average Nepali purchased 2.7 pairs of shoes a year, according to market research by the Footwear Manufacturers Association of Nepal.

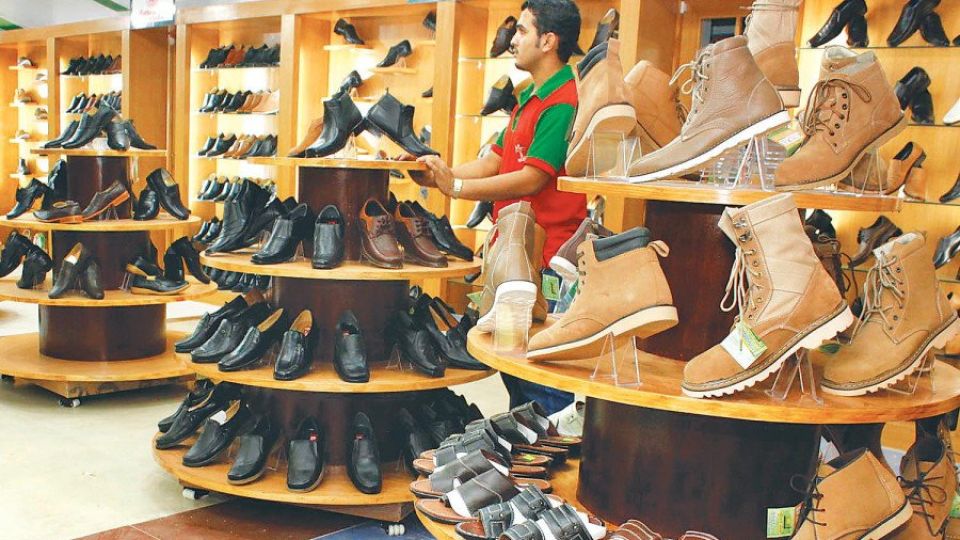

Industry associations and manufacturers reported that despite rising demand for foreign brand-name shoes, especially in the sports and casual shoe segment, the popularity of local brands was rising by leaps and bounds.

After Covid, Nepal saw a massive youth exodus, and the manufacturers lost their key customers, dampening the growth of the burgeoning footwear sector.

The association now estimates that the average Nepali citizen purchases less than two pairs of shoes a year due to the drop in their incomes.

Amid such problems, according to the manufacturers, there has been a new phenomenon in the footwear sector—rising imports of low-cost products and growing smuggling.

“The market is now flooded with low-cost footwear. Alongside the cheaper products, smuggling has thrived. It looks like the domestic industry is now struggling to remain afloat,” said Rudra Prasad Neupane, president of the Footwear Manufacturers Association of Nepal.

“We have estimated that a staggering 50 percent of footwear in Nepal is supplied by the grey market or parallel imports. This translates to an estimated loss of Rs11 billion in taxes for the government annually.”

The association’s recent research estimates that the annual demand for footwear in Nepal is 100 million pairs, over a threefold rise from the pre-Covid demand. But despite the staggering growth in demand, domestic manufacturers are struggling to survive.

Neupane, chairman of Run Shoes, said footwear manufacturers have been switching to trendy products after the demand for traditional products has dropped.

“There is a growing demand for trekking shoes and white sneakers. We, too, have been producing new designs suitable to meet the current market demands,” Neupane said.

According to Neupane, his company produces an average of 1,000 shoes and 1,500 sandals daily, a 25 percent reduction from a few years ago.

It used to manufacture up to 3,000 pairs a day. It has now halved the production. His factory employs 200 workers.

Other shoe brands are also adopting new methods to tide over the crisis.

Caliber Shoes recently collaborated with artist and singer Vek to produce a new line of footwear.

Dinesh Shrestha, regional distributor of Black Horse Shoes, said that the recurring losses have dampened their annual profit. “The footwear consumers have dropped significantly, particularly for domestic products. The availability of cheap footwear in the market is another factor that discourages us.”

They are facing losses month after month, said Shrestha

Exports, too, seem disappointing.

In the last fiscal year 2022-23, footwear was the only Nepal Trade Integration Strategy (NTIS) product to show a drop. Shipments fell by 12.46 percent to Rs990.84 million.

The key market of Nepali footwear is India with approximately 99 percent of the

export. According to the Trade and Exports Promotion Centre, in 2015, Nepal was the third biggest trading partner of India for footwear, with an import growth rate of 317 percent over the past 5 years.

Given the dynamics of the footwear sector, the government of Nepal included the sector in NTIS in 2016 as one of the 12 priority sectors.

In July 2017, the domestic footwear industry looked promising. Nepal saw annual sales of around Rs30 billion worth of footwear, including shoes, sandals and slippers. As the market grew, the contribution of locally-made footwear to the domestic market also increased. In the fiscal year 2015-16, more than 1,500 shoe factories, established at a cost of around Rs20 billion, manufactured almost 44 million pairs of shoes, sandals and slippers. The share of Nepal-made footwear products in the domestic market surged to 50 percent, from 20 percent in 2010.

The downfall in the footwear market started with the Covid pandemic, which forced hundreds of footwear manufacturers out of business as there was no need for new shoes and slippers when people were confined to their homes during the months-long lockdowns.

When the market opened, Nepali manufacturers were surprised.

There was a significant upsurge in the imports of shoes from India after Chinese imports to Nepal almost stopped.

“The imported shoes from India were so cheap that many domestic manufacturers, particularly the smaller ones, folded up,” said Shrestha.

Shikhar Shoes, one of the leading brands, is on the verge of a collapse.

“We suffered losses of Rs20 million during the lockdown period. There is no sign of a revival,” said Ram Krishna Prasai, managing director of Shikhar Shoes.

“We had 700 employees in our heydays. Now, the workforce has reduced to 50,” he said, adding that their production capacity has shrunk to 20 percent.

Prasai said that while the demand for the brand has not shrunk drastically, a severe shortage of working capital is another reason behind the poor health of footwear manufacturers.

Despite the shoes being made in Nepal, the raw materials are primarily imported from China, Singapore, India, and Malaysia. About 60 percent of raw materials are imported.

Neupane, the president of the association, said that due to the negligence in border inspection and lax implementation of rules and regulations, illegal imports have put Nepali manufacturers on the edge.

He said that the association has been lobbying foreign ambassadors to secure deals to export Nepali footwear to various countries.

“We are running a campaign called ‘Singha Durbar Bhitra Nepali Jutta’ [Nepali shoes in Singha Durbar],” said Neupane. Singha Durbar is the central secretariat of the government. “Our campaign is focused on requesting all the civil servants, ministers and ward chairpersons to opt for Nepali shoes with their formal attire to promote the Made in Nepal brand.”

“We need protectionist measures just like in India.”

京公网安备 11010202009378号

京公网安备 11010202009378号